Having survived the Covid crisis, in 2024 the Bulgarian beer industry turned the challenge of the last few years, in the words of the Executive Director of the Union of Brewers in Bulgaria (UBB) – into opportunities. UBB is a proud member of Brewers of Europe. We have already talked about the Brewers of Europe in the very first edition of the book, the premiere of which was honored by their then President! The Brewers of Europe, with all its members, is one of the most influential branch organizations carrying a certain weight within the official European institutions.

And speaking of them, in one of their capitals, Strasbourg, I came across the exhibition ‘The survival of antiquity…through advertising’. Familiar, isn’t it? Here are its Bulgarian beer dimensions. We find them both in the brands and in the symbols accompanying them. Unfortunately, in recent times, some of the brands have been left out, despite the raging „socialist nostalgia“. Maybe it’s because they’re not „socialist“, or maybe it’s because few people of my generation or older harbor nostalgia for socialist brands, outside of those available at Balkantourist, the national touristic organization.

As a matter of fact, one of the few sectors with normal privatization and without earth-shattering scandals was the beer sector. At that time the Union of Brewers in Bulgaria was established, which in turn became active members of the Brewers of Europe in the year after our accession to the EU. And the very next year, 2009, thanks to them, with the illustrator of the first edition of the book, we were received in their headquarters in Brussels.

We can’t help but be proud that for many years, in surveys of the reputation of the beer industry in the EU, Bulgaria has always been at the top – first or second after the Czech Republic. What greater proof of the weight of the UBB?

The first part of this chapter talks about the symbols used in brands up to 2009, when the book was first published. The stylized Thracian lion, either standing or on four paws, has greeted us from all Zagorka products since 1969. Even his tail is curled in the initial letter above the traditional symbols – ears of barley. A little further west, another Thracian city also erects two lions around its symbol – Hisar Kapia, the eastern fortress gate of old Plovdiv. Again, in socialist times, designers persisted in inserting either a mug or a goblet into its entrance. It was at this time that the brands Almus (one of the rulers of Volga Bulgaria), Istar (white, going east and at the same time similar to the Babylonian goddess Ishtar), Odessos (water city, Carian origin), Astika (after the Thracian tribe Asti, at the same time a play on words with the Indian term for divine origin) were born.

Monuments from the first to the third Bulgarian kingdoms we find among the symbols of the Shumen region – the Madara’s Horseman (years ago there was also Madara beer) and the former products of Bolyarka – then it was called Veliko Tarnovo (the penultimate Bulgarian capital) and one of its best examples was Staroprestolno. Bolyarka itself is indicative enough of its noble name. As a matter of fact, its slogan „Three centuries of brewing tradition“ had briefly appeared, replaced by the more accurate „Centuries of brewing tradition“. Let us recall that the founder, Mr Hadzislavchev, has been on the books since 1892. The boyar Dobrotitsa was for a short time the name of a Zagorka 10%, bottled in Dobrich in the 1990s… Sofia breweries (while they existed) offered the respective Serdika and Sredets, both old names of the town.

The euphoria of celebrating the 1300th anniversary of the Bulgarian state did not pass the beer by. Apart from the eponymous 1300 years, produced all over Bulgaria, old fonts replaced the ordinary ones, the special thing about Kamenitsa being the rather long tongue of the ale, both in the red and green versions of the 10% caps, as well as in those of Rhombus, and the Kamenitsa 100 anniversary (1981). Then the stylized beer glass with the letter K appeared. A similar plot stares back at us from the only German label – Kameniza bier – where a picture of the Old Town is in the alafrang, and on the bottle neck label floral motifs in gold asymmetrically flank the castle door. Speaking of Rhombus, let’s not forget that this is one of the names of Maritza. While the cap still relies on the old typeface (most notably in the diphthong ou – pronounced both Rhombus and Rhombous), the labels are all…rhomboid or with a stylized siren holding a cornucopia (1969-72). Now Rhombus is the name of the independent brewery at the entrance to Pazardzhik, which is also mentioned later.

Tracing the old Bulgarian script inevitably leads us to the Markovo Beer label with a Thracian chariot separating the year of foundation, 1881. This is one case, another episode of history to fit into the patriotic use of beer. The same chariot is also on the label of the premium beer Plovdiv. To the rare brands of beer and their respective symbols we add Eumolpia – the Thracian settlement on whose site Philip built his city. This time, a stylized head with a laurel wreath and a Greek profile looks back at us from the label. There is no way not to note the full correspondence of these historical features with the current slogan of Kamenitsa „Every sip has a story“.

The centenary of the Shipka Epic was celebrated with Shipka beer, produced both in Bulgaria and in Russia (then the USSR). For the record, the current Shipka is a „label“ product of Lomsko. At the same time, but under the name Druzhba (friendship), the anniversary was also celebrated by Shumensko. Thus history became an invariable advertising ploy, from antiquity to the recent past.

Even the last new small breweries (like the one in Pleven) after the game with the atamans bet on Storgosia – the name of the old Thracian settlement near Kaylaka. As a matter of fact, Pleven is also the name of a microbrewery in Finland (Plevna, in Tampere’s downtown), where a large number of those fighting in the Pleven epic are from. It will be discussed at the end of this chapter. And all the way in Buenos Aires there is a microbrewery called Cerveceria Búlgara.

Thracian was a short-lived brand of impersonal beer for a commercial chain from the now-defunct Sofia brewery (formerly Lyulin, even more formerly Macedonia), and Thracia was among the first of the brewery’s more ordinary products in Haskovo, when Astika was upmarket, unlike now.

The other geographical area with a transitional place in Bulgarian beer history is Mizia, a local product for the Pleven region of Almus (Lomsko). A glance at old Bulgarian beer labels will be enough to realise the local character of the dark beer in Pirin region such as Belasitsa (а neighbouring mountain) and the light Predela (а mountain pass), as well as for Emona – the Burgas original – there was also such a category between light and special. It is logical to look for maritime elements in the beers of the coastal towns of Burgas and Varna. An older image from Burgasko was a sailing ship, and a newer one was a combination of an anchor and rudder. A Greek ship was briefly the symbol of Odessos, an anchor – for Galata, and until recently the lighthouse from the eponymous cape adorned Varnensko – one of the products of Ledenika MM. But they too have been consigned to history, and not in the best way, given their infamous last owner.

It also seemed to be one of the few breweries not relying on history but on nature (the other was Pirinsko). Both the bat from the eponymous cave at Ledenika and the horse at Pirinsko are among the comparatively less common animals – beer symbols. It’s a pity that after the acquisition of Pirinsko by Carlsberg, the rare but hop-rich premium beer Golden Stag, which drew rave reviews at one of my first meetings with beer connoisseur collectors in the Netherlands in 2001, was discontinued. The protected Edelweiss, on the other hand, gives its name to the unsuccessful first Bulgarian low-alcohol (6.5% dry matter) beer in the 1970s. As a matter of fact, both it and the long extinct Black 13% and Porter 18% after the end of the 60s were brewed in Stara Zagora and Shumen – breweries respected at the time by the entire Bulgarian population and, unfortunately, equally hard to reach for most of it and especially for the capital’s citizens.

And now for the promised Finnish brewery with a Bulgarian name. Plevna, or the little-known dimensions of an epic. In 2009 I had the good fortune to represent Gueorgui Kornazov’s trio at the Sofia Days in Helsinki, and after the concert and the official part we went looking for a place that would fit the idea of Jazz+ „la noche es joven“ (the night is young). The night before I had received a small gift from our hostess – beermats from a microbrewery in Tampere with the very meaningful name Plevna on them. Despite the information that I was unlikely to find their beer outside Tampere, I couldn’t help but look for it in Helsinki’s richest beer bar. They had tried one of their beers there – a champion at the 2007 Helsinki Beer Festival – but there was no way they were going to risk a keg with so many bottled foreign beers. I left the story for another time and we had a real sahti.

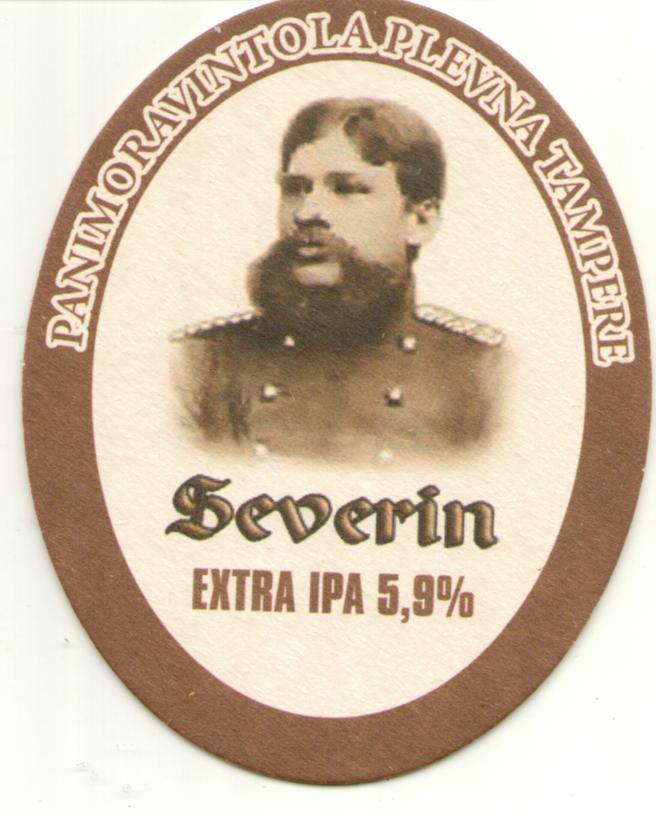

Some time ago, by chance, a colleague from the National Radio and I were discussing the side effects of the Russo-Turkish war and she asked the audience what they knew about the finer points. Everyone was awkwardly silent, except me, who apologetically broached my favorite subject and told her about a pub somewhere in Finland named after Pleven. The details had faded from my memory, but not from hers, and the next day I received a CD of Chapter 6 – Tampere – from her play, A Longer Road to the Battlefield. Daniela’s team is tracing the fate of Severin, one of the 223 participants in the epic, on the way back. Roy and a few other workers from the Scottish cotton mill Finlayson go to the battlefield, the mill having expanded in the meantime and the new buildings, as was customary, being given a name associated with a significant event. This is how the Plevna building came to be, where Tampere’s first microbrewery was established in 1994, long after the cotton factory had closed.

The radio play documents moments in the brewing process, from the whistling of the kettle to the pouring of some of the twelve beers into glasses, and Plevna also makes three types of cider and mead. A stout, Siperia (dedicated to the Trans-Siberian Railway), is one of the “1001 Beers You Must Try Before You Die” book; there’s also recently been a certified organic bock, and a natural highlight is the beer of the year, an extra IPA with a memorable name and image: the Severin. The radio (and their website) don’t reveal which of the C hops is used, but they do say that the first starter on the menu is the rusk (€4) – the most precious thing to Severin and his companions. For the more cultured, they could also be called bretzels. In any case, it’s a place to remember.

Their beers are certainly more worthy than the 1977 Bulgarian-Soviet experiment Shipka, whose cap doesn’t say whether it was brewed in Pleven, Stara Zagora or wherever, while the Moscow label is from the factory in Khamovniki.

Here’s Russian blogger Pavel Egorov’s description: “Khamovniki also has a branded bar where Topvar and unfiltered Khamovnicheskoe are poured. Tsar Cannon and Shipka beer with a new label design are also available. Khamovniki beer has an even stronger flavor of bad tap water, although if you get used to it, you can drink it.“

After 2009, some of the best home brewers closed the amateur side and embarked on adventures that put Bulgaria on the world craft map. Together with the last breweries registered and operating in the country, the total number of breweries in the country will be 40 by the end of 2023, according to official data from the Union of Bulgarian Brewers. Of these, 31 are microbreweries, six are small and medium-sized breweries and three are large breweries. Our average consumption is 80 liters per person per year. A few comparisons with EU member states not far away, with similar traditions but not similar populations, speak for themselves: in Greece there are 75 breweries with an average consumption of 35 liters, in Romania 96/83 liters, in Croatia 109/89 liters and in Hungary 75/68 liters.

The terms I used in the first edition – artisanal beer – have long since been swept away by the law of linguistic economy. Unless they are part of the name of a brewery, such as Kazan-Artisan. In most cases, the sense of a new reality also leads to new marketing to better identify the products of small Bulgarian breweries and microbreweries on the increasingly crowded shelves of craft bars and specialty shops. Few are those that put the local in the foreground (Chiprovsko, Avren, which add their postcode).

The Britos brewery in Veliko Tarnovo has a name that is more Thracian than British. In addition to the history of the name, the label also communicates the constant German control over raw materials and production. Against the backdrop of the advertising budgets of the international giants with subsidiaries in this country, betting on a wide drinking electorate, Britos is a white swallow with its uncompromising champion’s bitter taste (around 60 IBU) and the natural carbonation of the two-liter PVC, which I was later happy to see replaced by half-liter or even 0.33-litre glasses, in a design still used in Germany today.

Otherwise, even in supermarket chains with excellent value for money, you can regularly find Britos’s experiments with smoked malts, rosés and other flavors once described as „exoticOtherwise, even in supermarket chains with excellent value for money, you can regularly find Britos’s experiments with smoked malts, rosés and other flavors once described as ‘exotic“.

The situation is similar with the pioneers of Glarus (Slanchеvo, Varna) and to some extent Rhombus (Ivaylo, Pazardzhik). Glarus rely on the generic names of their respective styles, with the exception of so-called „short series/signatures“ such as „squirrel hops“, a pun on the hazelnut flavour of their boozy brown ale and the electronic game of the same name.

Rhombus also prefers to be explicit, but with an element of mystery (the personalities of the brewer’s wife and the „consigliere“ are reflected in this choice).

Blek Pine, who started out as serious homebrewers in a garage, liked a black cone from a Greek beach, and the photo design of a brewer’s wife gave the rest away. The misspelling of their name is deliberate, as is that of the Cohones, whose rooster-shaped silhouette makes them recognisable even to foreigners. Both breweries rely on strong but drinkable DDH (double dry hopping).

Wild Beer says it all in its name, and we find a similarly sought-after humorous alliteration in the aforementioned Kazan Artisan. The good thing is that almost every one of them is a first for the Bulgarian market in some way. Some of the biggest in terms of volume are UBB members (Britos, Glarus).

So far, alterations between big and small are very rare, and there is no sign of the typical US and European takeover of small companies by masters with offers that cannot be refused.

Personal histories (Three and Two), musical tastes (Metalhead) and again local pride (Hills, Danube, Melthum) only add to the ever-beautifying landscape where there has long been room for both “white storks” and “Averys”, albeit cooked out.

The city’s experiments in technology’s jokes are also well worth a look, from Sofia Electric to Rocket Science. As the latter likes to joke, „Who says that brewing beer isn’t space science?“

Towards the end of 2023, Sofia got another family-run microbrewery, which also offers beer vending machines for installation in public places (who’ll be the first?)

I cannot fail to highlight the solidarity of craft brewers in actions such as „I Am Amazing“ in support of the sector during COVID, and their second action of the same name in support of Ukraine after the barbaric aggression of Putin’s Russia. Those who participate in events to raise funds for the treatment of one of their emblematic colleagues also deserve admiration.

homebrewers competition

Of course, the opportunities offered by Meltum (and, from the end of 2023, Wild Beer) to brew the recipes of the winners of the homebrew competitions are also wonderful, not to mention that homebrew champions without their own brewery have also had the opportunity to brew for new craft breweries (Maya in Cohones).

Some of the collaborations – Sofia Electric with Mikkeller – have already been mentioned, unique beers are unique, and it’s nice when seasonal successes return, even if they’re not „updated“ (Glarus, Rhombus, Blek Pine).

Craft beer bars and tasting rooms deserve to be included in European beer guides for specialised tourism, and we can only regret the short-sightedness of the new management of Sofia airport, which has a lot to learn, from Brussels to the Valencian duty free shops, not to mention the Munich airport microbrewery Air-Brau and the Italian craft beer bars in the terminals of even small airports such as Turin (Balladin) and Bergamo (the bar remained after the closure of the microbrewery that created it, Elav).

It is no coincidence that the big names in the country’s big companies, in the „Beer in Focus“ series of the Bulgarian Brewers Association, insist on beer culture and work with young colleagues to experiment with new developments.

In the same direction is the „House of Beer“, created by Bolyarka, where visitors can get to know the history as well as the present and taste freshly brewed beer. A little later, the „World of Zagorka“ museum was opened, where we all wondered why the unfiltered beer that ended the visit could not be tasted elsewhere.

Kamenitsa went even further with the opening of Frick’s – the craft brewery under the preserved chimney of the Plovdiv brewery. Named after the brewery’s founders, Frick and Sulzer, the master brewer is the consulting editor of the first edition of this book, Ivan Karagyozov. I presented their Spiced White with Savoury at the Barcelona Beer Festival and there wasn’t a single taster who wasn’t enchanted. Since October 2023, their venue has been run by the team behind Sofia’s successful outdoor music club Maimunarnika – a head-turner for beer and music.

The attempt to match the cuisine is also noticeable, with places offering traditional German appetizers (Jägerhof – Plovdiv) as well as more intriguing homemade meats and other local specialties (Rhombus – Pazardzhik).

Beer lounges and other UBB events often feature chefs with excellent offerings, turning the shared beer into a gourmet experience.

These trends, together with the increasing and well-deserved place of women in breweries, large and small, which are also penetrating small and medium-sized settlements in our country, can and should be skillfully used by Bulgaria as a tourist brand. All the breweries in the country appreciate the growth of beer culture, especially among travelling young Bulgarians, but also among their traditional consumers.

It is clear that risky sudden moves are not as easy for the giants as they are for small breweries and microbreweries; the most important thing is that there is enough choice for every beer lover, and at a fairly good value for money in the EU. The Brewers’ Union green initiatives „We choose a sustainable future“, „CODE: Responsible together“, „Give me back“ for the collection of recyclable packaging are commendable. For these and many other campaigns, Bulgarian brewers have won a number of awards in social responsibility competitions. The most significant are also reflected in the international industry publication „Brew Up“.

Among the new trends in recent years, the literal outbreak of so-called „label“ brands should not be overlooked. In the case of Lomsko, we have witnessed a veritable explosion of regional, sporting and all sorts of other references, made to order by distributors on various occasions, including as a perpetuation of the Prosek brothers after their old brewery in Sofia was demolished to make way for a shopping mall on the square named after them.

Blek Pine, in turn, has adapted its recipes to the labels of partner bars, amongst others. The phenomenon is ubiquitous in Europe, with breweries everywhere labelling their beers for the big chains – mostly German and Belgian for the Italian market, and the Christmas holidays in Spain were marked by an „invasion“ of craft beers in large formats with big chain labels, to the benefit of all. What a pleasure for collectors of labels and cans (caps with inscriptions are rare) – the beer is drunk, but the materialized memory remains!